How to Be a Bad Emperor Read online

HOW TO BE A BAD EMPEROR

ANCIENT WISDOM FOR MODERN READERS

How to Be a Bad Emperor: An Ancient Guide to Truly Terrible Leaders by Suetonius

How to Be a Leader: An Ancient Guide to Wise Leadership by Plutarch

How to Think about God: An Ancient Guide for Believers and Nonbelievers by Marcus Tullius Cicero

How to Keep Your Cool: An Ancient Guide to Anger Management by Seneca

How to Think about War: An Ancient Guide to Foreign Policy by Epictetus

How to Be Free: An Ancient Guide to the Stoic Life by Epictetus

How to Be a Friend: An Ancient Guide to True Friendship by Marcus Tullius Cicero

How to Die: An Ancient Guide to the End of Life by Seneca

How to Win an Argument: An Ancient Guide to the Art of Persuasion by Marcus Tullius Cicero

How to Grow Old: Ancient Wisdom for the Second Half of Life by Marcus Tullius Cicero

How to Run a Country: An Ancient Guide for Modern Leaders by Marcus Tullius Cicero

How to Win an Election: An Ancient Guide for Modern Politicians by Quintus Tullius Cicero

HOW TO BE A

BAD EMPEROR

An Ancient Guide

to Truly Terrible Leaders

Suetonius

Selected, Translated, and Introduced by

Josiah Osgood

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright © 2020 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to [email protected]

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Suetonius, approximately 69-approximately 122, author. | Osgood, Josiah, 1974- translator. | Suetonius, approximately 69-approximately 122. De vita Caesarum. Selections. English | Suetonius, approximately 69-approximately 122. De vita Caesarum. Selections.

Title: How to be a bad emperor : an ancient guide to truly terrible leaders / Suetonius ; selected, translated, and introduced by Josiah Osgood.

Description: 1st. | Princeton : Princeton University Press, 2020. | Series: Ancient wisdom for modern readers | Includes bibliographical references and index. | In English and Latin.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019026869 (print) | LCCN 2019026870 (ebook) | ISBN 9780691193991 (hardback) | ISBN 9780691200941 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Emperors—Rome—Biography—Early works to 1800. | Rome—History—Empire, 30 B.C.-476 A.D.

Classification: LCC DG277.S7 O84 2020 (print) | LCC DG277.S7 (ebook) | DDC 937—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019026869

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019026870

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Rob Tempio and Matt Rohal

Production Editorial: Sara Lerner

Text and Jacket Design: Pamela Schnitter

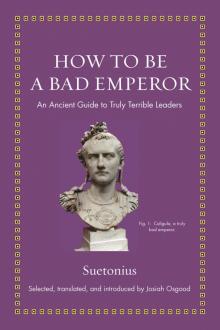

Jacket Credit: Bust of Caligula (Gaius Julius Augustus Germanicus), AD 12–41, 3rd Roman emperor. Rome, AD 37–41. Marble.

Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen. (Photo by PHAS/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

CONTENTS

Introduction vii

Ignore Bad Omens . . . and Your Wife: Julius Caesar (100–44 B.C.) 1

Spend All Your Time at Your Resort: Tiberius (42 B.C.–A.D. 37) 33

Make Your Horse a Consul: Gaius Caligula (A.D. 12–41) 121

Fiddle While Rome Burns: Nero (A.D. 37–64) 199

Acknowledgments 271

Notes 273

Further Reading 285

INTRODUCTION

“As president in the White House, a man becomes himself, squared—his hyperself, flaws and virtues enlarged by world attention and brought to fulfillment by the nature of the work and the power, and by the inescapability of the buck that stops on the desk in the Oval Office.”1 So journalist Lance Morrow has argued, in the introduction to a book about three American presidents, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Richard M. Nixon. The Roman biographer Gaius Suetonius Tranquillius, though he could not have known about the White House or Oval Office, and could not have understood “the buck that stops,” would have found himself in firm agreement with Morrow’s basic point.

As the selections included in this book show, Suetonius believed that once in power, the emperors of Rome felt free to indulge their own passions and pursuits, no matter how weird or reckless. “The moment Nero became emperor,” Suetonius writes, “he summoned the lyre-player Terpnus, considered the best at the time, and for days on end sat by him after dinner as he sang late into the night.”2 Little by little, Nero began to sing himself—to the horror of his domineering mother, Agrippina, and his tutor, the philosopher Seneca. Similarly, already as a schoolboy Nero had an enthusiasm for racehorses, but “in the early days of his rule” he started sneaking off to the Circus as much as possible.3 Soon enough, he wished to drive chariots himself.

Power unmasked the true identity of emperors. It brought to light quirks and vices that, as Suetonius saw, make for fascinating reading. In his biography of Tiberius, we see the emperor retreat to the beautiful and isolated isle of Capri, where it was easier to ignore public affairs and “give free rein to all of the vices that he had badly concealed for so long.”4 Not only does Suetonius catalogue these faults—including hard drinking, sexual perversion, and cruelty—in horrifying detail. He reveals that they were a part of Tiberius’ nature all along. Long before Tiberius became emperor, his army buddies had spotted his love of drink and joked about it. His rhetoric teacher, too, had put his finger on Tiberius’ cold, harsh nature. Even Tiberius himself, Suetonius suggests, peered into his own soul and glimpsed the monster he would later become—or, in truth, already was.5

Although he was writing about emperors, Suetonius was determined to provide more than a rehashing of major historical events. He wanted readers to see what emperors were really like, in private as well as in public. So he tells the famous story of Julius Caesar’s brutal murder on the Ides of March. But he also tells us about Caesar’s dining habits and sex life, his physical health and appearance. Small observations matter: Caesar was always irritated by his baldness, because he could be mocked for it, and he was thrilled when he was voted the right to wear a laurel crown on all occasions. Before then, he had been forced to rely on a comb-over. Readers have fun with juicy details like these. They make Caesar seem like a real person. They also help us to grasp Caesar’s arrogance and vanity, and understand how those qualities ultimately led to his catastrophic end.

The way Suetonius organized his lives helped him to avoid recreating standard histories. While he does typically start with an emperor’s family background, birth, and life up to the point of gaining power, and end with the emperor’s death and the omens foretelling it, the central part of each biography is organized not chronologically, but topically. In this main section, Suetonius might talk about the emperor’s public policy, his games and shows, and his building projects; but also, after that, his family and friends, his sense of humor and hobbies, his religious practices, and his health, appearance, even sleep habits; and then, too, his arrogance and disrespectfulness, his cruelty, his sexual excesses, his extravagance and greed. This allowed Suetonius to showcase details that might be hard to fit into a linear narrative. Moreover, the Lives of the Caesars include altogether twelve emperors, beginning with Julius Caesar (Caesar’s successor Augustus nowadays is more commonly regarded the true firs

t emperor) and ending with Domitian. Thus the reader can easily compare one emperor to another, and see similarities and differences. While the bad emperors featured in this book—Julius Caesar, Tiberius, Caligula, and Nero—have much in common, Caligula emerges as far worse than Tiberius. Tiberius at least tried to hide his cruelty; Caligula wanted to flaunt it.

For all the care with which he collected and catalogued details of emperors’ lives, Suetonius was not aiming for an objective presentation. He is not afraid to include what he knew were only rumors. “There was . . . a set of rumors,” Suetonius writes, “that Caesar was going to move to Alexandria or Troy, taking all of the empire’s money with him.”6 Nero allowed nobody to leave the theater while he was singing, “and so some women, it is said, gave birth during his shows.”7 Caligula loved his racehorse Incitatus so much that he gave him a house, slaves, and furniture, and “it is even said he planned to make him consul.”8 Such vivid images, even when identified as hearsay, stamp themselves on reader’s minds. They are almost the equivalent of modern political cartoons.

The way Suetonius classifies information also is designed to persuade the reader. To cover first, briefly, the positive aspects of Nero’s rule and then, at far greater length, his “disgraceful and criminal acts” clearly accentuates the negative.9 Romans had a tendency to satirize their late emperors, and Suetonius’ comments may reflect storytellers’ efforts to one-up each other more (or less) than sober reality. In reading what follows, one is free to ask: did Tiberius endorse a man for public office because he drank six gallons of wine at a party?10 Did Caligula wear a beard made out of gold to look like Jupiter, or carry a trident as if he were Neptune? Did Nero sing through an earthquake that shook the theater he was in?11 Or are these more political cartoons?

Suetonius was not making things up himself, but he may have relied on material not strictly reliable. Yet there can be little doubt that he was convinced that emperors had the ability to do both great good and great harm. Augustus, the paradigmatic good emperor of Lives of the Caesars, beautified Rome, improved its infrastructure, restored its religion, and promoted discipline in the army, among other accomplishments. Bad emperors, in contrast, by succumbing to vice, not only indulged themselves—they neglected the defense of the empire, they inflicted food shortages on the people of Rome, and they robbed, tortured, and murdered members of the Senate, not to mention their own relatives. They stripped others of their dignity and beat them into submission. As the bad emperor’s own personality was magnified into a grotesque “hyperself,” to use Morrow’s term, those around him risked losing their identity altogether.

An anecdote Suetonius tells about the emperor Domitian (who ruled A.D. 81–96) illustrates the biographer’s sense of imperial power.12 Ruthless in raising money, Domitian insisted that the Jewish poll tax be enforced fully. The tax had been imposed on Jews after the Great Rebellion of 66–70, which had culminated in the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple. Suetonius recalls a man of ninety years old being hauled before the financial officer and a crowded court, where he was forced to strip, to determine if he was circumcised. If so, he would have to pay up. Thus an emperor’s decisions mattered.

Suetonius’ views were clearly shaped by his own personal experience. He was born around A.D. 70 into a wealthy family, perhaps from North Africa. His father, named Suetonius Laetus, was an equestrian—a member of the formally defined status group just below the Senate in prestige, which provided the Roman Empire with military officers and civil servants. Laetus fought as a legionary commander for Otho, one of the men vying to be emperor after the death of Nero. Though a career in the army was open to Laetus’ son too, the future biographer preferred to focus on scholarship. He produced a series of works in Greek and in Latin, now almost entirely lost, including Roman Spectacles and Games, The Roman Year, Words of Insult, and Famous Prostitutes. With the help of the Senator Pliny the Younger, he came to the attention of the emperor Trajan (who ruled 98–117) for his achievements.

It was probably Trajan who appointed Suetonius to his first positions in the imperial service as advisor on literary affairs and director of Rome’s public libraries. Under Trajan’s successor, Hadrian (who ruled 117–138), Suetonius rose to the important post of secretary of correspondence, in which he could observe just how much the decisions of an emperor, or his entourage, mattered. It was now that he finished and published the biography of Augustus: in it, Suetonius parades his closeness to the emperor.13 Later, though, Hadrian dismissed Suetonius from office, along with the head of the imperial guard, because they were more familiar with Hadrian’s wife than the emperor deemed suitable. The suggestion sometimes made that Suetonius had his revenge by crafting venomous biographies of Augustus’ successors seems unlikely, but the biographer’s fall is a vivid testimony to the court intrigues that Suetonius believed were at the heart of imperial government. In the pages of his biographies, mistresses, wives, astrologers, physicians, slaves, and even court jesters wield power through their closeness to the emperor.

What is the purpose of gathering together Suetonius’ stories of bad emperors? One answer is that they help to explain features of our own time. Our fascination with great power and with great personalities owes something to the Romans, even to the Lives of the Caesars in particular. Suetonius spawned many sequels in antiquity and beyond, and through translation and adaptation—including Robert Graves’ famous Claudius novels—he has given us a sense that to be a Caesar is to be outsize, outrageous, out-of-this-world. It is no coincidence that one of Las Vegas’ longest-running casinos is called Caesars Palace.

We are shocked by Caligula’s cruel putdowns or Nero’s mania for performance, but we also find their transgressions just a little bit pleasurable—find the men themselves almost entertaining. In the twenty-first century, we see better than ever how politicians can build movements around their personalities. Suetonius helps us to understand why. In giving free rein to their own desires, Caesars may tap into our hidden wishes too.14

But then they pull us up short. We see just how badly they dealt with the challenges they faced, for the buck did stop with them. In a reversal of the usual self-help formula, How to Be a Bad Emperor becomes a guide to how you can be a good leader, whatever your role in life. Caesar refusing to stand to greet the Senators when they come bearing honors: a lesson in how to treat colleagues. Tiberius trying to win glory from a disastrous fire: a reminder that you shouldn’t always try to take credit for your accomplishments. Caligula brutalizing those around him, even forcing his father-in-law to cut his throat with a razor: brutalize, and you will be brutalized back. Nero meeting the threat of rebellion by loading his wagons with organs for the theaters and concubines with buzz cuts: your pet projects may fatally undermine you and your organization.

Reading the Lives of the Caesars from cover to cover can be daunting, so many details are included. The stories of the bad emperors and the weird worlds they constructed make for an entertaining selection. They are also a meditation on how the acquisition of power may not so much corrupt, as the old adage has it, as allow our own worst qualities to slide out and harm us. Unrestrained power may be thrilling, but in the end proves ineffective.

HOW TO BE A BAD EMPEROR

Divus Iulius

IGNORE BAD OMENS . . . AND YOUR WIFE

Julius Caesar (100–44 B.C.)

While modern historians typically regard Augustus as Rome’s first emperor, Suetonius begins with Julius Caesar. Caesar, as he saw, did not just provide a name for his successors, along with some key precedents. His abuse of power was an anticipation of problems to come.

As Suetonius writes, Caesar was a gifted general. A superb horseman, he was always on the move, bareheaded in sun and rain alike. He could cover vast distances at incredible speed. If it suited him, he would join battle immediately after a march, even in bad weather. And if any of his soldiers started fleeing, he would grab them by the throat and force them back into the fray. He judged them purely by their fight re

cord—not their social standing or morals.

For all his toughness, though, he was vain. He kept his head carefully trimmed and shaved—and was accused of depilating certain other parts of his body that were hairy too. Nothing in life distressed him more than his baldness. Of all the honors he received, the right to wear a laurel crown pleased him most: he took advantage of it on every occasion.

Caesar had to be the best at everything—fighting, writing, even making love. His entire life he was a boaster. At his aunt’s funeral, as a young man, he bragged of his descent from gods and kings. After a battle in the civil war he initiated in 49 B.C. by illegally crossing the Rubicon River into Italy, he proclaimed “I came, I saw, I conquered.”

In the following selection Suetonius describes how Caesar’s arrogance brought him down. His outrageous remarks and shoddy treatment of senatorial colleagues stirred up deadly feelings of hatred, and his supreme self-confidence blinded him to signs of trouble, including clearly alarming omens. A modern reader might dismiss much of Suetonius’ account as superstition. But “Beware the Ides of March” remains a warning today for leaders about the danger of ignoring advice.

76. Yet others things he said and did tip the scales, leading to the judgment that he abused his power and was justly killed. It was not just that he accepted excessive honors: a continuous consulship, the dictatorship for life, and the censorship of morals, as well as the first name “Imperator,” the surname “Father of his Country,” a statue among the kings, and a raised seat in the theater. He also allowed honors to be awarded to him that were too great for any human being: a golden throne in the Senate-house and in front of the speaker’s platform; a wagon and litter for processions in the Circus; temples; altars; statues next to those of the gods; a cushioned couch; a flamen; priests for the Lupercalia; the naming of a month for him.1 Indeed, there were no honors he did not receive, or bestow, as he liked.

How to Be a Bad Emperor

How to Be a Bad Emperor